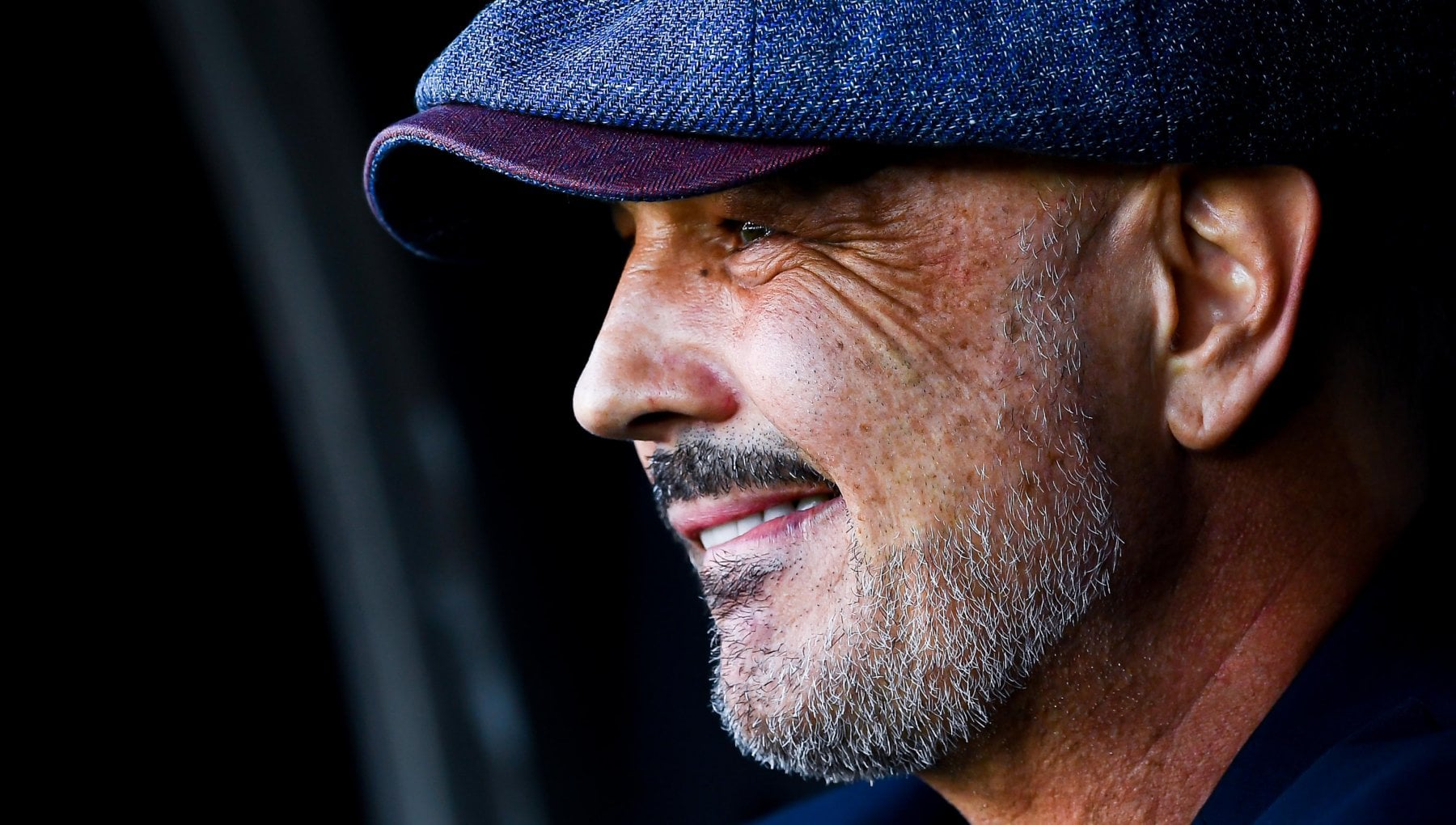

The last thing that Sinisa Mihajlovic would want, even now that he has lost his battle with leukemia, is to be commiserated. That is exactly what he said when he held a press conference in the Summer of 2019 to announce that he had been diagnosed with it: “I am not here to get your sympathy.”

There was one really touching moment during that meeting with the press. It was when he let out a few tears, promptly adding that “these are not due to fear” (No doubt, Sinisa). It was when Mihajlovic reflected on how he realized that this was really happening to him: “Everybody would think I could not catch anything, big and strong as I am. But no one should ever think of himself as being indestructible.”

Perhaps, that is the last and most important lesson left by Sinisa Mihajlovic, the Serbian Sergeant, an almost-unstoppable free-kick shooter as a player, feared and respected as a football coach. More than his straightforwardness. More than his “fight hard, fight fair” credo. Just a humbling lesson about the transience and fragility of life.

Sinisa Mihajlovic was born in Vukovar, a town that became a time bomb when the Croatian War of Independence escalated. He was the son of a Serbian father and a Croatian mother and was extremely proud of his roots, including his gypsy heritage. He took this sense of national belonging terribly seriously, so much to the point that he kicked Adem Ljiajc out of the Serbia squad roster when he was the head coach because he refused to sing the National Anthem.

His personality was a blend of pride, honor, and rugged integrity, where an old-school sense of manliness jumbled up with some polarizing nationalistic positions, many of which were forged during the Balkan Wars in the early 1990s.

A good portion of his heart, however, was also Italian. Mihajlovic spent most of his professional career, both as a player and as a coach, in the land of calcio, and was perfectly fluent in Italian. In the Belpaese, he found love and raised five beautiful kids.

But before landing in Italy, he did witness the horror of war at home. Mihajlovic left his hometown very young to make a career in football, and as much as that could be an example of “growing up fast,” it was in no way comparable to what the term meant for many of his fellow countrymen during the Yugoslav Wars.

Mihajlovic once recalled coming back to his hometown when he already was a professional player. He found his old house destroyed and saw something that would stick in his mind forever: “Two kids, standing there, holding assault rifles. They must have been 10 or 11 years old. What really stroke me was their eyes. They were the eyes of an adult, but still in a kid. The sad eyes of some kids who did not live their childhood.”

Mihajlovic had made his way up to Crvena Zvezda, the “Red Star” of Belgrade and the top Yugoslav club. He was part of a golden generation of players that took Crvena Zvezda to the top of Europe, winning on penalties the European Cup 1991 Final against Olympique Marseille.

Mihajlovic had his moment of glory in the second leg of the Semi Finals when he helped his side eliminate Bayern Munich with a surprising brace. One of his goals came from a freekick, of course.

The time in Belgrade made him forge some influential, yet controversial friendships with some of the key figures in the Balkan conflict, including Crvena Zvezda ultras chief turned paramilitary force leader Zeljko Raznatovic. Mihajlovic would never recant his ties with the ill-famed war criminal Arkan, who once reportedly spared one his Croatian uncle’s life in view of their friendship.

When the Yugoslav football movement fell apart, the then 22-year-old defender crossed the Adriatic Sea to join Roma, lured by his compatriot coach Vujadin Boskov. He would become one of the very few players to play for both clubs of the Italian capital, even though he spent much more time at Lazio and once claimed that “My heart is definitely Biancoceleste.”

Sinisa did not have many good memories of his first two Serie A seasons with the Giallorossi. However, he did live some remarkable moments even at Roma. He was the one who, on March 28, 1993, suggested his coach Boskov to make Francesco Totti debut. “Coach, put the boy in!”, he suggested as Roma were leading 2-0 in Brescia, pointing at that 16-year-old youth club striker whom Boskov had just aggregated to the senior team.

As a player, Mihajlovic was probably one of the best freekick takers ever seen in Serie A. His left foot was absolutely devastating. He did not have Alessandro Del Piero or Andrea Pirlo’s grace, no. Mihajlovic was pure power.

It was after leaving Roma to play four years with Sampdoria, and then six more with Lazio, that his fame as a lethal free-kick taker arose, along with the echo of his strong and pretty short temper. “People say you should count to 10 before doing something. In the beginning, I did not count at all,” he once remarked. “Then I started to count to 2 or 3, and I manage to reach 5 or 6 now. But I don’t think I will ever come to 10.”

Whenever Lazio were awarded a free kick, Sinisa’s smirk as he positioned the ball was enough to intimidate even the most seasoned goalkeepers. His secret, as he would eventually recall, was staring the opponent goalies in their eyes and take a short run-up always in the same way, to avoid giving any point of reference. Then, just one second before shooting, Mihajlovic would decide where exactly to fire the ball. That generally meant somewhere in the back of the net.

On December 13, 1998, he became the second player in the history of the top Italian flight to score a hattrick all via free kicks in a Lazio 5-2 win over Sampdoria. The poor goalie Fabrizio Ferron’s face as he caught the ball in the net for the third time was priceless. In that 1998/99 season, Mihajlovic scored eight goals playing as a defender.

The Lazio days were his most successful in Italy. With the Biancocelesti, he won the final edition of the Cup Winners Cup in 1999, and Lazio’s second and to date last Scudetto the following season. Those were also the days of his fiercest battles on the pitch, a place where Sinisa never backed up. The most remarkable one was a slugfest with his young compatriot Mateja Kezman, who played for his old crosstown rivals Partizan Belgrade and whom Lazio faced in a Cup Winners Cup matchup.

Much less memorable was a clash with Arsenal’s Patrick Vieira in a Champions League group stage match that ended in a regrettable exchange of insults between the two. Vieira accused the Serbian of racial abuse. Mihajlovic eventually apologized but remarked that his insults were in retaliation for being called a “gypsy piece of s***” by the Frenchman.

The “gypsy piece of s***” insult was a painful constant in the life of Sinisa Mihajlovic. His detractors resorted to it whenever they wanted to push his most important buttons, those related to his origins.

Mihajlovic commented with pride that the derogatory part of the insult was the “s***” line, not the “gypsy.” He also noted that nobody had ever dared to call him like that while facing him. That says a great deal about Sinisa’s personal “code of conduct,” according to which it did not necessarily matter what you said if you said it face to face.

When he became a coach, he could not but make himself a name as an “Iron Sergeant.” His short temper, together with his dedication and work ethic, made him the coaching nemesis of those millennial starlets who seemed to lack the dedication and grit he needed. Mihajlovic did not hesitate to leave out of the Milan squad Mario Balotelli as he was not showing the right attitude in his view.

Another good example was Stefano Okaka Chuka, a Nigerian-Italian striker who never fully lived up to his talent. Mihajlovic coached him for one year and a half while holding the reins at Sampdoria. Things were great initially as Okaka scored 5 times in his first 13 appearances with the Blucerchiati. However, their relationship gradually deteriorated and Okaka left Sampdoria following a violent altercation with the coach.

Defender Daniele Gastaldello recalled the episode and reported that Mihajlovic literally lifted Okaka and pushed him out of the locker room. “It was something I had never seen. When Mihajlovic loses it, you better stay away from him.”

When he was training Torino, Mihajlovic once exploded against midfielder Joel Obi, who asked to be substituted due to cramps after 60 minutes in a 1-2 loss to Inter. Sinisa, who had already made two changes, did not like it for a bit and made it clear to the press: “He’s young, he’s a Serie A player, and he can’t have only 60 minutes in his legs. If my midfielders cannot run for more than 60 minutes, then they should rather work in accounting or play futsal with their friends.”

With his teammate Daniele Baselli he was even more straightforward after subbing him in a game against Pescara: “I pulled him out because he wasn’t giving me anything. I have been telling him for three months that he needs to grow some balls if he can.”

When a journalist once praised Marco Benassi, noting how it was not easy to be the captain of Torino at only 22, Mihajlovic’s answer was exemplary: “Waking up at 4.00 AM to start working at 6.00, and still struggling to make ends meet, THAT is not easy. Being the captain of Torino at 22 is a pleasure and an honor, and Benassi must be happy about that (…) because he’s a lucky person like all of us who do this job.”

One thing that Mihajlovic did not lack for sure was an eye for talent and the courage to reward it. When he was at Milan, he had the merit of making a 16-year-old Gianluigi Donnarumma debut, turning him into the Rossoneri starting goalkeeper. Once again, he had the courage of believing in a promising young kid, just like 23 years earlier at Roma with Totti.

The last chapter of Sinisa Mihajlovic’s story is a recent one. He was called at Bologna’s deathbed in January 2019, with the club second to last in Serie A with only 14 points. He managed to save the Rossoblu collecting an impressive 30 points in the remaining 17 games.

He remained at the helm until a few months ago, splitting himself between the dugout and the hospital as he fought his personal battle with leukemia. He taught us to be strong and to stay true to ourselves, to remember that we are mortals and therefore to live our lives to their full extent until the last day. For that we thank him. For that, and for the deadliest freekicks ever seen in Italian football.